South and Central Asia

Naga Shawl Weaving originating from Nagaland, the 16th state of the Indian Union, is a rare art form passed down through generations, with Naga women mastering the art on looms during the agricultural off-season.

Naga women predominantly use red or black yarn, occasionally infused with dark blue hues. Cotton and wool are favored materials, although the decline of cotton cultivation in the state has shifted weavers towards store-bought supplies. The motifs are intricately embroidered in a densely patterned weave and are unique to each tribe.

These shawls are not mere garments but intricate expressions of Naga traits, professions, honors, and entitlements. Despite the rich heritage of the Naga Shawl, it’s a fading art as quality yarn is hard to come by, leading to financial instability for the weavers.

Pattachitra originated in Odisha, India and has a rich legacy of over 3000 years. Etymologically, the term "Pattachitra" translates to a picture or painting on cloth, paper, and palm leaves, depicting songs, stories, and folklore from the region.

Pattachitra Art is deeply rooted in Hindu mythology and artists work in a familial setting. The head artists create outlines while women prepare glue, canvas, and fill the paintings with colors. To achieve its unique texture, the canvas is rubbed with a mixture of chalk and tamarind seeds, providing a distinctive leathery finish.

Renowned Pattachitra artist, sculptor, and Padma Shri awardee, Raghunath Mohapatra, has left an indelible mark on the art form. But due to a lack of recognition and patronage in recent times, this art form has been declining.

The origins of Dokra (or Dhokra) can be traced back to the tribal communities of Bastar in Chhattisgarh, India. The name of the craft is believed to be derived from the Dhokra Damar tribes, who have been perfecting this art form for generations.

Dokra artifacts, crafted from brass or bronze, use the lost-wax casting method. The artisans create intricate wax models, covering them in clay and then melting the wax to pour molten metal into the mold.

The labor-intensive process, rising costs of raw materials, and a pandemic-hit market have made it hard for the artisans to sustain their livelihoods, making Dokra an endangered art form.

Naga Shawl Weaving originating from Nagaland, the 16th state of the Indian Union, is a rare art form passed down through generations, with Naga women mastering the art on looms during the agricultural off-season.

Naga women predominantly use red or black yarn, occasionally infused with dark blue hues. Cotton and wool are favored materials, although the decline of cotton cultivation in the state has shifted weavers towards store-bought supplies. The motifs are intricately embroidered in a densely patterned weave and are unique to each tribe.

These shawls are not mere garments but intricate expressions of Naga traits, professions, honors, and entitlements. Despite the rich heritage of the Naga Shawl, it’s a fading art as quality yarn is hard to come by, leading to financial instability for the weavers.

Pattachitra originated in Odisha, India and has a rich legacy of over 3000 years. Etymologically, the term "Pattachitra" translates to a picture or painting on cloth, paper, and palm leaves, depicting songs, stories, and folklore from the region.

Pattachitra Art is deeply rooted in Hindu mythology and artists work in a familial setting. The head artists create outlines while women prepare glue, canvas, and fill the paintings with colors. To achieve its unique texture, the canvas is rubbed with a mixture of chalk and tamarind seeds, providing a distinctive leathery finish.

Renowned Pattachitra artist, sculptor, and Padma Shri awardee, Raghunath Mohapatra, has left an indelible mark on the art form. But due to a lack of recognition and patronage in recent times, this art form has been declining.

The origins of Dokra (or Dhokra) can be traced back to the tribal communities of Bastar in Chhattisgarh, India. The name of the craft is believed to be derived from the Dhokra Damar tribes, who have been perfecting this art form for generations.

Dokra artifacts, crafted from brass or bronze, use the lost-wax casting method. The artisans create intricate wax models, covering them in clay and then melting the wax to pour molten metal into the mold.

The labor-intensive process, rising costs of raw materials, and a pandemic-hit market have made it hard for the artisans to sustain their livelihoods, making Dokra an endangered art form.

South-East Asia and Asia Pacific

Lombok pottery is a timeless craft passed down through generations by the people of Lombok, an Indonesian island located east of Bali. The island is home to several villages known for their pottery production, including Penujak and Banyumulek.

Lombok pottery is made by processing clay into items such as vases, plates, and other household items. The pottery is often decorated with intricate designs that reflect the cultural heritage of the people of Lombok.

Lombok pottery was initially utilitarian, producing functional vessels for daily use. As tourism and cultural exchanges grew, Lombok pottery adapted to cater to a deeper audience, incorporating more intricate and decorative designs.

Saa paper umbrella making is a traditional handicraft of creating handmade umbrellas using Saa paper (made from the bark of the mulberry tree). The umbrella-making process, native to Thailand, involves treating the mulberry bark to soften it, then grinding and boiling it to create a fine pulp to make the paper. The paper is then cut and designed into the shape of the umbrella and supported by a bamboo frame.

Bo Sang, a town near Chiang Mai in northern Thailand, is a prominent destination for its Saa paper umbrella-making heritage and hosts an annual Umbrella Festival to showcase the work of local Saa artists.

Despite the aesthetic appeal of Saa paper umbrellas, challenges in accessing broader markets for their handcrafted umbrellas have impacted the economic viability of the craft.

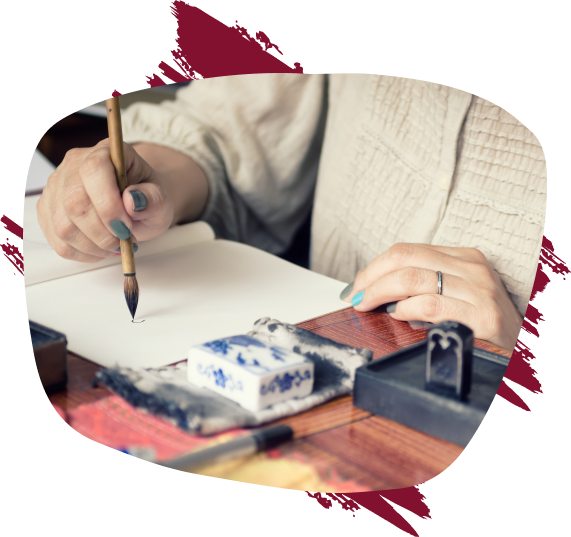

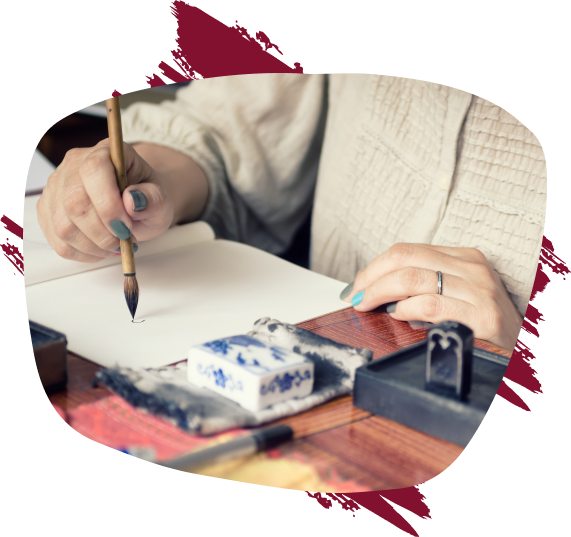

The expensive Sumi-e ink is the traditional black ink used in Japanese calligraphy and ink-wash painting. Originally, artisans made the ink with soot from burned pine wood and combined it with animal glue or other binding agents to shape it into sticks. The Sumi-e ink stick was then rubbed on an inkstone with water to produce vibrant ink for writing or painting.

Sumi-e ink artisans produce the ink when the temperature and humidity are optimal. A minimum of four years is required for production—and the most expensive ones take even longer. The best time to make Sumi ink is from autumn to early spring when the air is dry and cold.

The rise of commercial inks and the intricate production of Sumi-e ink puts it at risk of decline. Masako Yamamoto, the artist behind the Koho School of Sumi-E, has helped to delay this fate and popularize Sumi-E artworks across the globe.

Lombok pottery is a timeless craft passed down through generations by the people of Lombok, an Indonesian island located east of Bali. The island is home to several villages known for their pottery production, including Penujak and Banyumulek.

Lombok pottery is made by processing clay into items such as vases, plates, and other household items. The pottery is often decorated with intricate designs that reflect the cultural heritage of the people of Lombok.

Lombok pottery was initially utilitarian, producing functional vessels for daily use. As tourism and cultural exchanges grew, Lombok pottery adapted to cater to a deeper audience, incorporating more intricate and decorative designs.

Saa paper umbrella making is a traditional handicraft of creating handmade umbrellas using Saa paper (made from the bark of the mulberry tree). The umbrella-making process, native to Thailand, involves treating the mulberry bark to soften it, then grinding and boiling it to create a fine pulp to make the paper. The paper is then cut and designed into the shape of the umbrella and supported by a bamboo frame.

Bo Sang, a town near Chiang Mai in northern Thailand, is a prominent destination for its Saa paper umbrella-making heritage and hosts an annual Umbrella Festival to showcase the work of local Saa artists.

Despite the aesthetic appeal of Saa paper umbrellas, challenges in accessing broader markets for their handcrafted umbrellas have impacted the economic viability of the craft.

The expensive Sumi-e ink is the traditional black ink used in Japanese calligraphy and ink-wash painting. Originally, artisans made the ink with soot from burned pine wood and combined it with animal glue or other binding agents to shape it into sticks. The Sumi-e ink stick was then rubbed on an inkstone with water to produce vibrant ink for writing or painting.

Sumi-e ink artisans produce the ink when the temperature and humidity are optimal. A minimum of four years is required for production—and the most expensive ones take even longer. The best time to make Sumi ink is from autumn to early spring when the air is dry and cold.

The rise of commercial inks and the intricate production of Sumi-e ink puts it at risk of decline. Masako Yamamoto, the artist behind the Koho School of Sumi-E, has helped to delay this fate and popularize Sumi-E artworks across the globe.

Middle East & North Africa

Globally recognized for their elaborate patterns, lively hues, and superior craftsmanship, Moroccan Berber rugs hold a prominent status. These rugs mirror the profound bond between the Berber people and their homeland.

The wool used in crafting Berber rugs comes from the sheep and goats raised by the Berbers, which are then hand-spun into yarns. Natural dyes extracted from plants, minerals, and insects are sourced locally to color the wool. The weaving process, usually practiced by women artisans, boasts a distinct character, making them unique.

Traditionally, Berber carpets were offered as a present to those in the upper social classes in the Imperial Cities of Morocco and other emerging nations. Museums like the Dar Batha Museum host many historic Berber rugs from Morocco that are still revered.

Mashrabiya wood carving is a traditional woodworking technique used to create intricately carved latticework panels and is a signature feature of Islamic architecture. Like Islamic mosaic tiles, mashrabiya patterns feature interlocking shapes, showcasing a blend of beauty and geometric complexity.

Mashrabiya serves as a passive cooling system, channeling air through lattice openings. Traditionally, these ornamental window treatments were designed to mark off gender boundaries within interior spaces while offering shade. In Islamic principles, mashrabiya evolved into a platform for showcasing artisanal and decorative skills within the permissible confines of realistic imagery.

In this age, Mashrabiya wood carving is a relic of aesthetic beauty and cultural significance. One popular representation of Mashrabiya intricacies is prominent in Susan Hefuna's artwork, "Woman Cairo 2022."

Sadu weaving is a traditional weaving style practiced by Bedouin women in Middle Eastern countries like Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates. The term "Sadu" comes from the horizontal-style weaving technique used to create woven textiles with distinctive geometric patterns and designs.

Originating in the Arabian Peninsula, Sadu weaving was traditionally a functional craft used by Bedouin nomads to make practical items like tents, rugs, and camel bags. The weaving involves a warp-faced plain weave crafted on a ground loom. The resulting fabric, made using natural fibers and sourced locally by the community, is tightly woven and robust.

Master weavers, typically older Bedouin women, are the primary custodians of Sadu. Objects created using Sadu weaving techniques underscore the significance of female roles within Bedouin society.

Globally recognized for their elaborate patterns, lively hues, and superior craftsmanship, Moroccan Berber rugs hold a prominent status. These rugs mirror the profound bond between the Berber people and their homeland.

The wool used in crafting Berber rugs comes from the sheep and goats raised by the Berbers, which are then hand-spun into yarns. Natural dyes extracted from plants, minerals, and insects are sourced locally to color the wool. The weaving process, usually practiced by women artisans, boasts a distinct character, making them unique.

Traditionally, Berber carpets were offered as a present to those in the upper social classes in the Imperial Cities of Morocco and other emerging nations. Museums like the Dar Batha Museum host many historic Berber rugs from Morocco that are still revered.

Mashrabiya wood carving is a traditional woodworking technique used to create intricately carved latticework panels and is a signature feature of Islamic architecture. Like Islamic mosaic tiles, mashrabiya patterns feature interlocking shapes, showcasing a blend of beauty and geometric complexity.

Mashrabiya serves as a passive cooling system, channeling air through lattice openings. Traditionally, these ornamental window treatments were designed to mark off gender boundaries within interior spaces while offering shade. In Islamic principles, mashrabiya evolved into a platform for showcasing artisanal and decorative skills within the permissible confines of realistic imagery.

In this age, Mashrabiya wood carving is a relic of aesthetic beauty and cultural significance. One popular representation of Mashrabiya intricacies is prominent in Susan Hefuna's artwork, "Woman Cairo 2022."

Sadu weaving is a traditional weaving style practiced by Bedouin women in Middle Eastern countries like Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates. The term "Sadu" comes from the horizontal-style weaving technique used to create woven textiles with distinctive geometric patterns and designs.

Originating in the Arabian Peninsula, Sadu weaving was traditionally a functional craft used by Bedouin nomads to make practical items like tents, rugs, and camel bags. The weaving involves a warp-faced plain weave crafted on a ground loom. The resulting fabric, made using natural fibers and sourced locally by the community, is tightly woven and robust.

Master weavers, typically older Bedouin women, are the primary custodians of Sadu. Objects created using Sadu weaving techniques underscore the significance of female roles within Bedouin society.

Are you loving what we do?

To know more about our adventures, say hello to us at hello@savedyingarts.com